Management of a child with a runny nose

Although it is unusual for children to complain about having a runny nose, parents very commonly do so on their behalf. There are a number of causes of rhinitis in children and the differential diagnosis changes with age. This article provides a diagnostic approach to paediatric rhinorrhoea and summarises management options for the more common causes.

History

Cases of rhinitis can be divided into allergic and non-allergic and salient features from the history usually enable your patient to be assigned to one of these two categories. Allergic rhinitis is suspected when there is family history of atopic illnesses or when a child with rhinitis has co-existent asthma or atopic dermatitis. Seasonality of symptoms, provocation of symptoms by exposure to aeroallergens (such as cat dander or house dust mite) and associated symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis all suggest an allergic basis for rhinitis.

Physical Examination

Frequent rubbing of the allergic nose can lead to the formation of a transverse crease across the nose and venous congestion of the lower eyelids may result in allergic shiners.

The nasal mucosa and septum may be examined by using an auroscope with a relatively large speculum. Physical findings typical of allergic rhinitis include pale pink or bluish grey mucosa over the inferior turbinates which are coated with watery secretions.

Examination with an auroscope may reveal polyps under the middle turbinates in cases of nasal polyposis or purulent secretions flowing over the inferior turbinate in infective rhinosinusitis.

Some judgement can be made about the patency of the nasal passages and whether there is significant septal deviation which may contribute to a feeling of nasal obstruction.

Differential Diagnosis

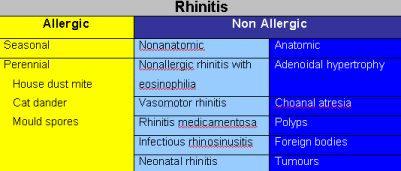

The differential diagnosis for paediatric rhinorrhoea is summarised in table below.

Allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis results from the production of allergen specific IgE. Exposure to an allergen in a sensitised child causes the release of inflammatory mediators such as histamine from the nasal mucosa, which causes clear rhinorrhoea, sneezing, itch and obstruction. In New Zealand seasonal allergic rhinitis is usually caused by sensitivity to grass pollen whereas perennial rhinitis is caused by house dust mite, pet dander and mould spore allergy.

Role of skin testing in the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis

Skin prick testing with aeroallergen extracts is useful in the management of rhinitis because it answers two questions:

- Is the patient atopic?

- Against which specific allergens has the patient produced IgE?

Management

The three modalities of management of allergic rhinitis are drug therapy, allergen avoidance and immunotherapy.

-

Drug Treatment

The most effective medication for the treatment of moderate to severe allergic rhinitis is the regular application of topical corticosteroid nasal sprays.

Oral and topical antihistamines are effective and particularly useful when the symptoms are intermittent such as on high pollen days because of their rapid onset of action. Second generation antihistamines are well tolerated but expensive medications. Antihistamines and nasal steroids have an additive effect.

Sodium cromoglycate nasal spray is less effective than nasal corticosteroids and has a short half-life necessitating three to four doses per day.

The usefulness of decongestant nasal sprays for the treatment of rhinitis is limited by the short period of time for which they can be used without the risk of developing rebound nasal congestion. However, use of a decongestant spray for the first few days of initiating treatment with topical corticosteroid sprays may increase the access of steroid spray into the nose. -

Allergen avoidance

A combination of history and skin prick tests will reveal which allergens are clinically relevant to a particular child. If the symptoms are perennial, the most common culprits are house dust mite, cat and mould spores. House dust mite exposure can be reduced by a few simple measures which can produce clinical improvement. The key manoeuvre is to encase the pillows and mattress in dust mite allergen impermeable covers. Bed linen should be hot washed weekly and blankets soaks in eucalyptus oil and detergent before warm washing every few weeks. Soft toys should be washed periodically and spend one day a week in the freezer. These manoeuvres are not expensive and can improve asthma and eczema as well as allergic rhinitis. It is best not to keep cats in the homes of atopic children, however it is difficult to convince families of the need to find alternative homes for their pets. Keeping the cat outside is a reasonable although poorly complied with compromise. -

Immunotherapy

Some severe cases of allergic rhinitis do not respond adequately to topical corticosteroids and antihistamines, and some allergens such as grass pollen are not easily avoided. Immunotherapy can be recommended in these circumstances. Immunotherapy involves the subcutaneous injection of initially minute amounts of allergen, with the dose increasing usually in a weekly basis to a large dose which when given regularly over a period of time switches off the immune hyperresponse to that allergen. Maintenance injections are usually given once every a month for a period of three years. Such a course of immunotherapy can bring about improvement which lasts for very many years afterwards. The repeated injections are not well tolerated by small children, and so immunotherapy is rarely given to children less than 10 years. The efficacy of sublingual immunotherapy is being actively researched. Some trial results suggest it may have a role to play in the future management of paediatric allergies.

Non-allergic Rhinitis with Eosinophilia

Non-allergic rhinitis is diagnosed when symptoms of perennial rhinitis are present but the patient is non-atopic (ie has negative skin prick tests to common aeroallergens). The nasal mucus contains high numbers of eosinophils. Non-allergic rhinitis may be associated with nasal polyposis and sinusitis, asthma and aspirin hypersensitivity (a combination of four features known collectively and inaccurately as the aspirin triad). In contrast to allergic rhinitis, non-allergic rhinitis usually begins in adulthood. First line treatment is with topical corticosteroids.

Vasomotor rhinitis

This condition is characterised by rhinorrhoea and nasal stuffiness which are provoked by physical stimuli such as exposure to cold air and hot or spicy food ingestion. Vasomotor rhinitis usually responds well to treatment with ipratropium nasal spray.

Rhinitis medicamentosa

This condition is uncommon in young children but adolescents may become chronic users of vasoconstrictor nasal sprays and develop a dependence on such drugs. Treatment involves withdrawal of the vasoconstrictor nasal spray and its replacement with topical corticosteroid preparations.

Sinusitis

Acute bacterial sinusitis is most commonly a sequela of a viral upper respiratory tract infection. The viral rhinitis leads to obstruction of the sinus ostia and subsequently to bacterial growth in the stagnant mucus trapped within the sinus cavity. Acute sinusitis usually resolves completely. However if there is persisting obstruction of sinus drainage the sinusitis may become chronic. Allergic rhinitis may in this way predispose patients to chronic sinusitis. Primary immunodeficiency disorders such as hypogammaglobulinaemia, cystic fibrosis and ciliary disorders are rare conditions which need to considered when children present with resistant cases of chronic sinusitis.

Signs of acute sinusitis in older children include facial pain, headache and fever. Younger children commonly present with rhinorrhoea and cough. Rhinorrhoea is sometimes minimal but there may be significant postnasal drip.

The diagnosis and extent of sinusitis can be confirmed with CT scanning. Microbiological testing is usually of little help as there is little correlation between the results of nasal swabs and maxillary sinus punctures.

Acute sinusitis is treated with antibiotics. Chronic sinusitis may respond to courses of antibiotics and topical or oral corticosteroids. Endoscopic surgery has been performed successfully in children but because chronic sinusitis tends to resolve as the child grows older surgery is performed less frequently than in the adult population.

Neonatal Rhinitis

Neonatal rhinitis is an idiopathic disorder characterised by noisy breathing, rhinorrhoea and poor feeding which presents within the first few weeks of life. The nasal mucosal oedema usually responds well to dexamethasone nose drops.

Adenoids

Hypertrophy of the adenoids may cause chronic purulent rhinitis which is often associated with other symptoms of upper airway obstruction such as snoring and mouth breathing. The adenoids are small at birth and enlarge over the first to fourth years of life as a result of increased immunological activity. Most children grow out of adenoid related problems by age 8 to 10 years. Unfortunately it is difficult to differentiate symptoms caused by adenoidal hypertrophy from those of perennial allergic rhinitis on the basis of symptoms alone. A child who mouth breathes is often labelled as having enlarged adenoids but this problem may well be caused by turbinate hypertrophy. Adenoidal hypertrophy may be diagnosed by flexible nasendoscopy (not tolerated by many children) or with a lateral neck X-ray. A poor response to medical therapy for rhinosinusitis may indicate that adenoids are playing a causative role for nasal symptoms.

Choanal atresia

This is the most common congenital anomaly of the nose. It results from failure of perforation of the septum which divides the nose from the pharynx (Figure 3). When bilateral it presents shortly after birth with respiratory difficulty and cyanosis as the neonate is an obligate nose breather for the first six to eight weeks. Airway obstruction is relieved when the mouth is opened to cry. Nearly half of the children who have choanal atresia have other congenital anomalies. Unilateral atresia may go undiagnosed until later in life when it presents with symptoms of unilateral nasal obstruction and discharge.

Nasal Polyps

Nasal polyps typically appear as bilateral glistening sacs (which look like peeled grapes) originating from the ethmoid sinuses. They are rare in children less than 10 years old and if found should instigate investigations for cystic fibrosis, or if present in the neonate for meningocoele or optic glioma (Figure 4). Nasal polyposis can also occur in children who have primary ciliary dyskinaesia. Nasal polyps are treated surgically. Recurrence is a significant problem which may be reduced by the long-term administration of topical corticosteroids.

Foreign Bodies

A unilateral purulent and usually malodorous discharge may result from a foreign body in the nose. Placement is frequently denied and the event may well have been forgotten.

Septal Deviation

Nasal septal deviation is seldom a cause of rhinorrhoea but may cause nasal obstruction. Septal deviation in children can be congenital or be a result of birth trauma.

Tumours

Tumours are a rare cause of rhinorrhoea, but unilateral symptoms and signs should prompt an examination of the nose. In adolescent boys nasal obstruction and recurring nosebleeds may be a sign of an angiofibroma, which although a benign tumour can become locally invasive.

Summary

Rhinitis in the paediatric population has a number of differential diagnoses. Features from the history and physical examination and results of investigations usually allow a specific diagnosis to be made. Once the nature of the rhinorrhoea has been determined, treatment can be tailored to the cause.

Practice points

- Rhinitis in the paediatric population can be divided into allergic and non-allergic cases. This distinction has important management implications.

- Skin prick testing is a very useful tool in distinguishing allergic from non-allergic rhinitis and for helping to identify which allergens a patient is sensitised to.

- Allergen avoidance is an important method of treatment for paediatric rhinitis (particular for house dust mite allergy).

- Nasal examination with an auroscope may help establish the diagnosis by identifying polyps, pus, foreign bodies etc.

Murali Mahadevan

Specialist ENT Surgeon

For all enquiries and appointments call (09) 925 4050

Suite 6, Mauranui Clinic86 Great South Roadd

Epsom, Auckland 1051

Facsimile: (09) 925 4051

Only general information is provided on this web site and is not intended as advice or a consultation. Please read our full disclaimer.